Bianca Smith is on a mission to find out how far her life-long passion for baseball can take her as a coach, and whether her fascination with Japan can make that happen in Nippon Professional Baseball.

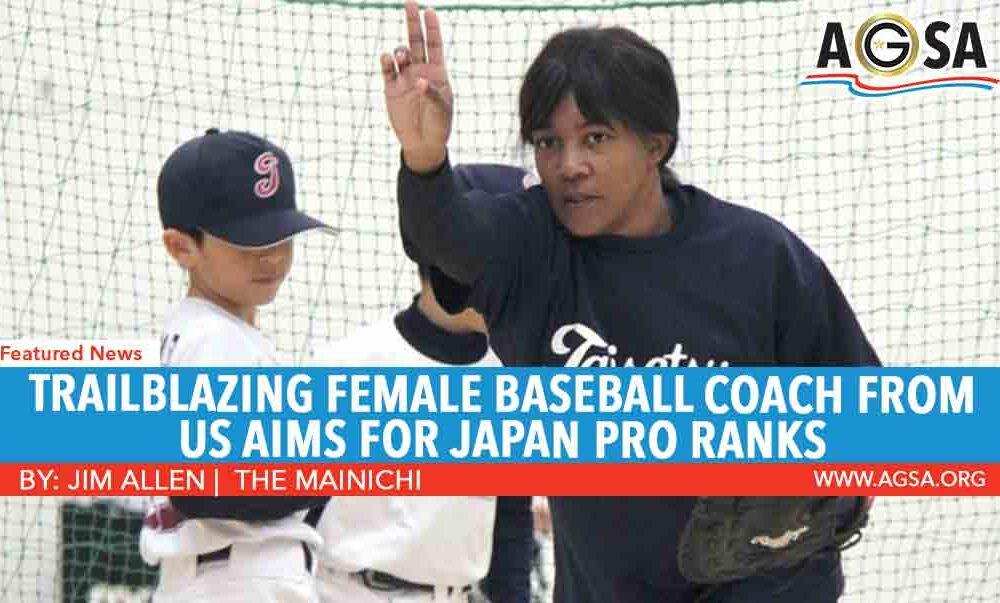

The first black woman hired to coach by a Major League Baseball team, Smith is now a world away from America’s minor leagues, in Japan’s northern main island of Hokkaido, working as a sports advisor and coaching elementary school and middle school teams.

With her degrees in business and law, the 33-year-old Smith once saw herself as a future MLB team president, but found her true calling in uniform on the field with players.

When the Boston Red Sox wanted to keep her at the lowest minor-league level for 2023, Smith opted to move on, not knowing a dream opportunity would shortly open up and bring her to Japan.

“I have been fascinated with Japan since I was 12, just like any American kid (through) anime. Then I started reading manga,” Smith said. “I fell in love with Japan, and when I decided I was going to work in baseball, that was top of my list.”

Turned onto baseball by her mother, a New York Yankees fan, Smith’s favorite player was Derek Jeter. She was alerted to a different style of baseball in Japan after Hideki Matsui joined the Yankees.

“I have been following the Japanese national team since the first World Baseball Classic in 2006. The aspects of Japanese baseball are what I’m passionate about, the defense, the base running, the strategy, that’s why I love watching them. That’s why Japan.”

In Higashikawa, Hokkaido, she’s sharing her knowledge and experience with kids and coaches but said it’s hard to tell when coaches and parents buy into her ideas or if they’re only open because the head coach is on board.

“That’s why I’ve got all the information together so I can explain why we need to do it this way. I’ve been picking and choosing,” she said, sounding like the lawyer she trained to be.

Smith’s coaching journey has been a process of learning how to manage her need to control things, and developing communication and teaching skills to better help players.

“I don’t want to come in changing the culture because that never works,” she said. “But I am a player coach. In the pros (in the United States) they’re used to this. Even the coaches that are territorial, they’ll still listen to players. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have a job.”

Despite her deep and sustained interest in Japan, Smith was not prepared for the ritual displays of respect she has witnessed toward coaches, parents and the field itself, or for the culture of fault finding.

“It’s one of the first things I saw. In a practice game, a kid makes one mistake, they pull them and make them practice for 30 minutes, next to the game, that same mistake they messed up,” Smith said.

When the head coach eventually asked how mistakes are dealt with in America, Smith told him.

“You put him back in,” she said. “You talk to him quickly and then put him back in. If they know that if they make one mistake they’re going to get pulled, they’re going to be afraid to make a mistake. They’re going to play it safe on every play.”

Smith has been willing to lead by example through her efforts to learn languages and communicate in them as best she can, mistakes and all.

How analogous is a willingness to make mistakes in a foreign language and a willingness to make mistakes in baseball?

“It’s completely the same,” Smith said. “You’re not going to get better if you don’t push your limits and try to go past them.”

Coaching kids has pushed her to be even better at simplifying techniques in order to demonstrate them.

“It comes in handy as a coach, particularly working with people who don’t speak your language,” she said.

“A good coach is able to take a complicated idea and simplify it for anybody. Being a lawyer is just like being a coach,” she said. “A lawyer has to break down the law for someone who doesn’t understand it and take the important parts that actually apply to them.”

As an advocate of the player-first coaching that is gradually making headway in Japanese pro baseball and who shares its compulsion to plan everything that can be controlled, Smith would seem to be an attractive hire for a Japanese pro team.

But she said, the team would have to genuinely want her to empower players to develop their own styles rather than lecture them on doctrine and dogma.

“I want you to take control of your own development because you know your body better than I do,” she said. “I could not coach for an organization that would not let me have that kind of freedom with my players.”

(By Jim Allen)